Today, I had the honor of presenting to the Congressional Rare Disease Caucus along with incredible fellow advocates and experts.

The rare disease community has faced considerable setbacks in the past four months. Without Congress taking action, the federal Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) will not grow. Without NIH funding, we will not see new treatments for ultra-rare conditions. Without an accelerated approval pathway and surrogate endpoints, treatments for rare diseases will be limited.

The price of inaction is the lives of children. Period.

Here is the recording from today’s briefing, along with a recording of only my speech.

Here are my slides and my remarks:

My name is Lesa Brackbill, and I have been a rare disease and NBS advocate for ten years. Like so many of my fellow advocates, I have chosen to turn our tragedy into triumph for others because of our great loss.

It is an honor to share today about this collective burden of a lack of access to treatment for serious and often terminal rare conditions on behalf of my family and those who have endured similar paths.

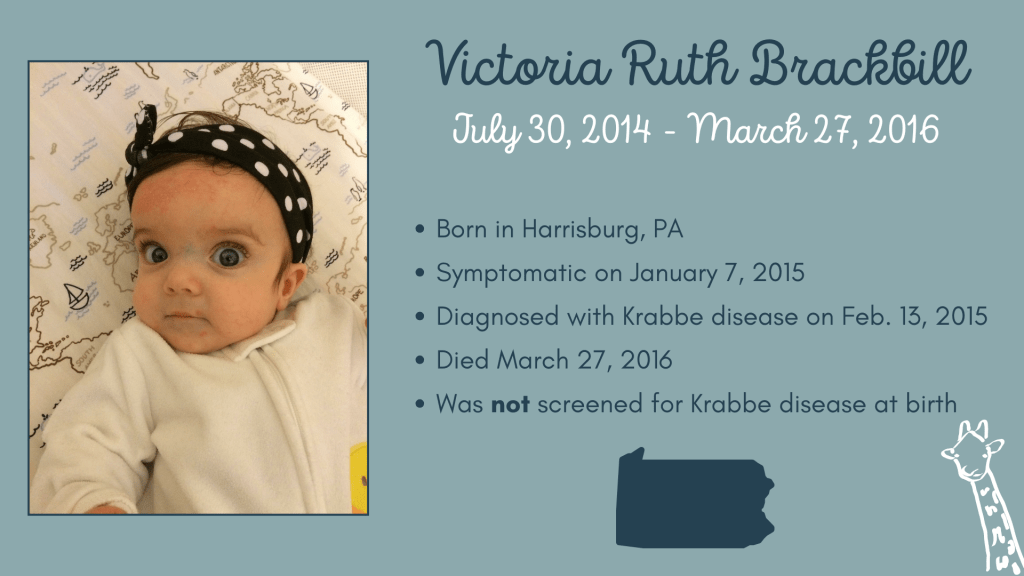

My husband and I both say that Friday, February 13, 2015, was the worst day of our lives.

We returned home the night before after a five-day hospital stay with our daughter, Victoria, after being told to expect results in two weeks. So when we received a call saying we needed to come in that afternoon, we felt a sense of doom.

It had been six weeks since our daughter, Tori, suddenly became symptomatic with something terrible. Six weeks of searching for answers, with bad news arriving with every test performed.

So the fact that they had an answer that required an immediate, in-person delivery made us wary.

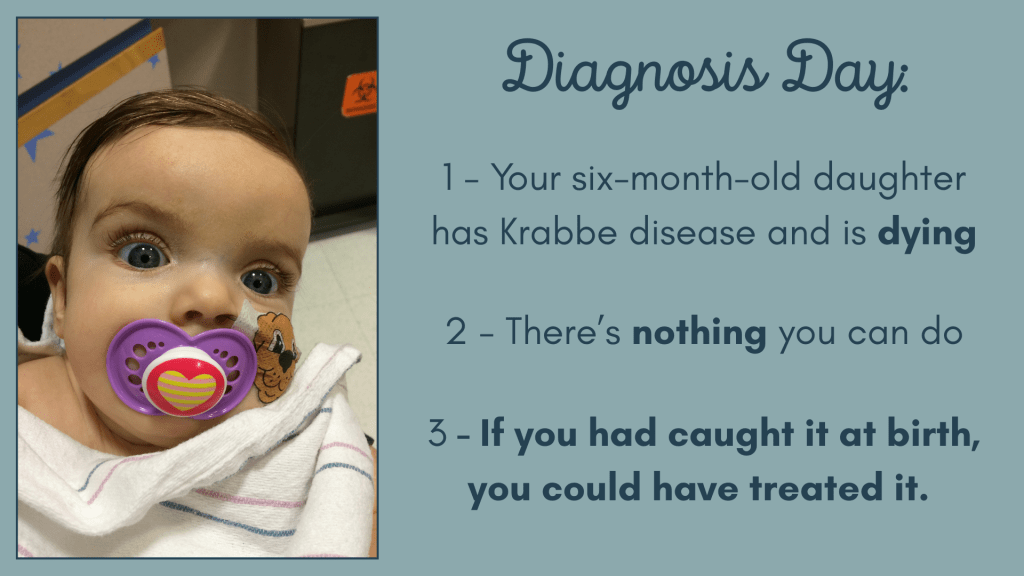

We were ushered into a typical exam room with beige walls intended to soothe, but even that couldn’t calm our anxiety that day.

We held our daughter while we waited for the neurologist to come in. When she did, we immediately knew the news wasn’t good. We could see it in her eyes. She shook our hands, and then gently said the two most terrible words we could have heard:

It’s Krabbe.

Only a week prior, right before Tori was admitted to the hospital, we learned that she had a form of leukodystrophy; against the neurologist’s wishes, we had Googled the term and saw a list of subtypes. We had seen Krabbe on that list, and we knew it was a death sentence.

Dying is not a word that should describe anyone’s six-month-old child.

She told us three things that day:

1 – Our six-month-old daughter had Krabbe disease and was dying

2 – There was nothing we could do

And when we pressed her on that, pleading for something, anything we could try, she said the words that haunt me to this day:

3 – If you had caught it at birth, you could have treated it.

Caught it at birth?

She briefly explained NBS and the access to treatment it provides, but noted that not all states screened for the same conditions.

In that moment, it became clear that advocacy was always supposed to be my story, my life’s work. Everything leading up to this moment – my political science degree, lobbying experience – finally became clear. I was supposed to effect change, to build her legacy.

I eventually came to accept that the loss of my daughter would result in the saving of countless others through Newborn Screening and early access to treatment. I had a moral imperative to advocate.

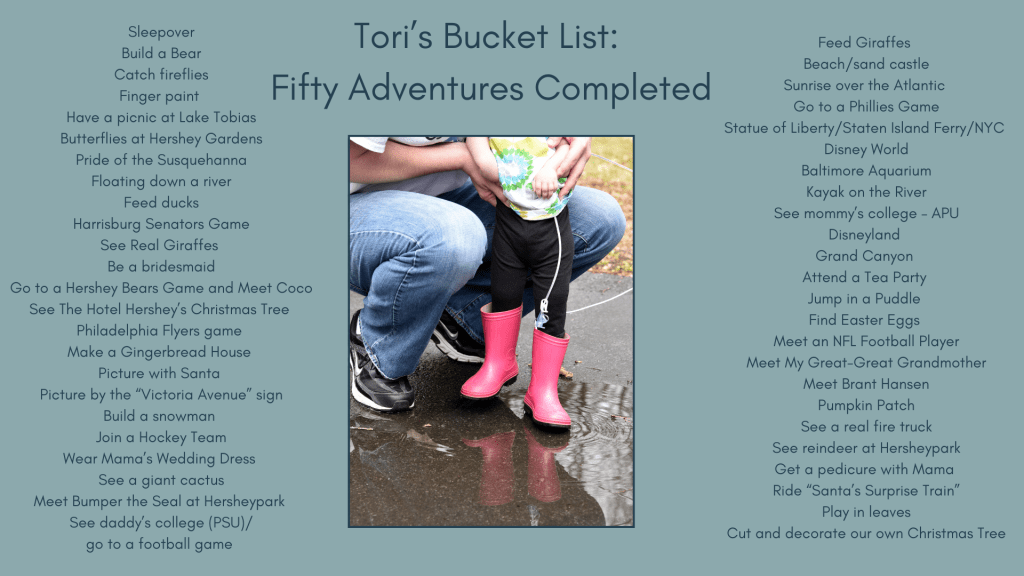

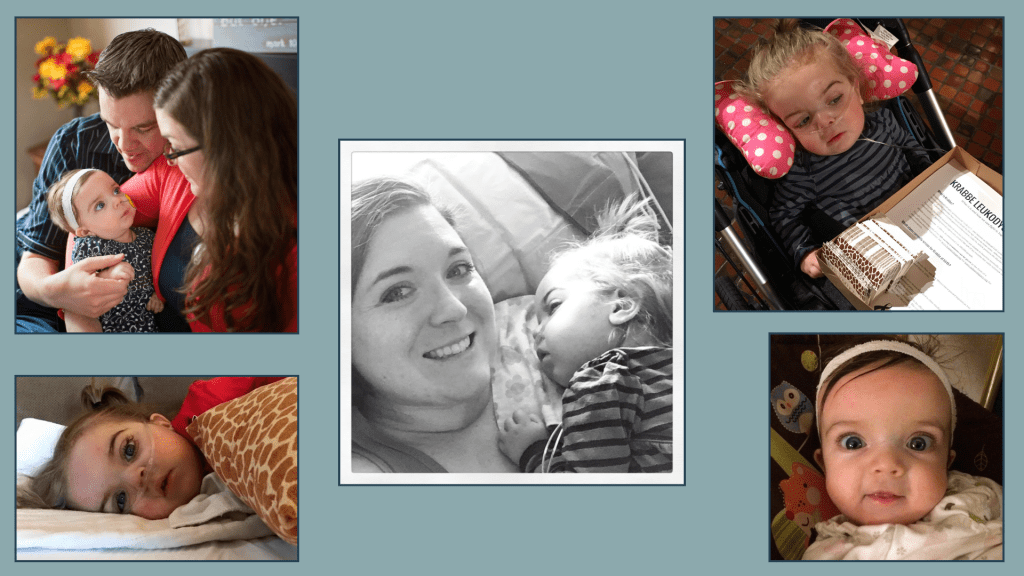

Despite this tragic news, my husband and I decided that we were going to LIVE with Tori while she was still with us, and we completed 50 bucket list items with her.

Of course, we also had to learn to be her caregivers, add a great deal of medical equipment and knowledge to our home, and provide round-the-clock care without the help of a home health nurse. But we did it.

We had so many adventures and chose joy during a time when it would have been easier to choose grief.

The time for grief would come – Tori died fourteen months later at just twenty months old.

That grief is what fuels the work that I do. Three weeks after her death, I began my advocacy journey. I attended a meeting of the PA NBS Advisory board and began to learn about NBS, how it worked in PA, and what I would need to do to make an impact.

Three bill attempts and five years later, I succeeded in reforming the PA NBS program with Act 133 of 2020.

Because of my advocacy, the advisory board chose to begin screening for Krabbe disease in May 2021; two months later, on Tori’s birthday, identical twins were born; a week later, they were diagnosed with Krabbe disease because of NBS. They were the first two to receive gene therapy for Krabbe, and it’s all because of Tori.

It felt like redemption.

Last year, I was involved with the process of seeing Krabbe disease added to the federal Recommended Uniform Screening Panel, a list that was created to increase uniformity between states for those born with rare, treatable conditions.

I watched as we worked through the process, as the ACHDNC demonstrated a willingness to work with the rare community to improve the process, and now, I’m watching as what little we had has been taken from us.

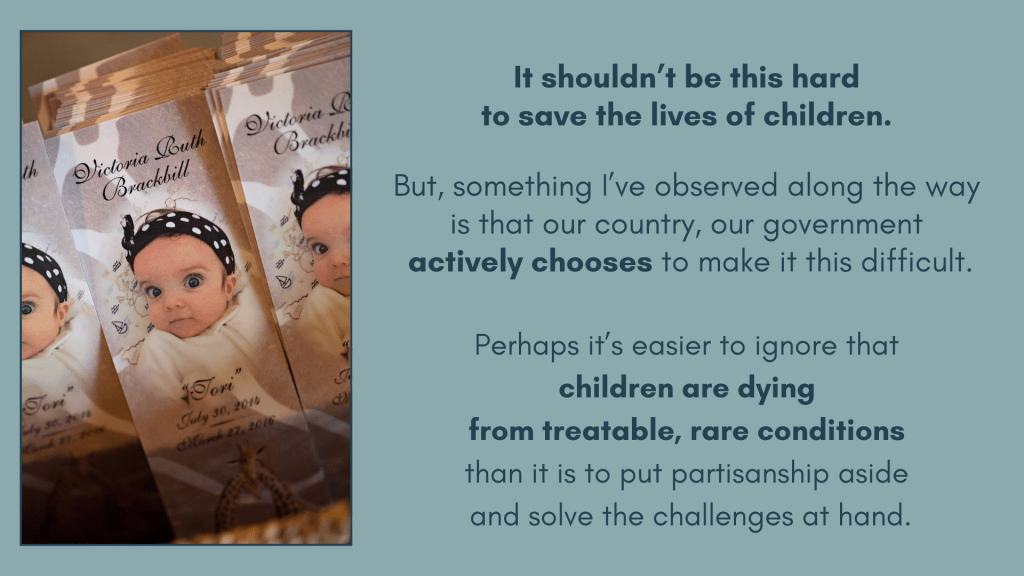

It shouldn’t be this hard to save the lives of children. But something I’ve observed along the way is that our country, our government, actively chooses to make it this hard. Rare disease advocacy is often met with roadblocks, goal posts being moved, and partisanship creating problems that shouldn’t exist. Problems like the lack of a process for adding conditions, because the committee was disbanded to save money.

Perhaps it’s easier to ignore that children are dying from treatable, rare conditions than it is to put partisanship aside and solve the challenges at hand.

The loss of the ACHDNC has been a devastating blow to the rare disease community. While it wasn’t a perfect pathway, it was something. It gave advocates a road map to follow for an evidence-based decision, not a legislative one.

It empowered us in the face of great loss. Without it, we are left feeling powerless once more.

I have experienced the powerlessness that comes from receiving a diagnosis with despair; a diagnosis discovered too late for action.

But I have also experienced empowerment by being able to help prevent that future for babies born in Pennsylvania and beyond. And the ACHDNC was the catalyst for those efforts.

I teach advocates eight essential components for effective advocacy: be willing to learn and respect expertise; listen to understand; operate ethically; communicate well and often; work flexibly and collaboratively; and give credit where it’s due. Taking action is a given. I advise them to embrace humility in their advocacy, communication, and lives as they work toward changing the NBS system.

However,

Advocacy only works when both sides are willing.

What we are experiencing now from the federal government is the direct opposite of those eight components; and,

We are watching the erosion of morality and ethics as diagnostic pathways for treatment-eligible newborns are being decimated.

Access to treatment is being denied.

You speak in terms of dollars saved, but the ultimate cost of these decisions is the lives of children.

Children like my Victoria.

Krabbe disease stole so much from Tori, and from us. It stole her smile, her voice, her big beautiful eyes, and ultimately her life.

My husband will never be able to dance with his daughter at her wedding, something that still makes him emotional at weddings we attend.

Our twins ask where baby Tori is, forcing us to have an impossible conversation with her brothers, who never had the opportunity to meet her. Now, she is represented in family photos by a giraffe, but it shouldn’t be this way. She should be here today.

We couldn’t save Tori, but advocating to provide access to early diagnosis and treatment gives us some peace because we are giving parents something that was taken from us: the opportunity to try to save their child’s life. And, as members of Congress, you have the power to make that possible for many.

Our twins ask where baby Tori is, forcing us to have an impossible conversation with her brothers, who never had the opportunity to meet her. Now, she is represented in family photos by a giraffe, but it shouldn’t be this way. She should be here today.

We couldn’t save Tori, but advocating to provide access to early diagnosis and treatment gives us some peace because we are giving parents something that was taken from us: the opportunity to try to save their child’s life. And, as members of Congress, you have the power to make that possible for many.

To conclude, “The depth of my love for my daughter is not measured by the number of tears I have cried, but rather by the life I choose to live in her absence.”

I choose to be relentless in advocacy, ensuring that NBS saves as many lives as possible. And it’s all for Tori.

But we cannot accomplish this goal without the help of Congress, and inaction is not an option.

Thank you.

Thank you for your brave advocacy. My own two daughters were diagnosed with a rare and treatable condition through newborn screening in the US, phenylketonuria. Preserving newborn screening must be prioritized as a moral imperative. Best wishes in your important work!

LikeLiked by 1 person